On the afternoon of Aug. 5, it was exactly 90 degrees outside in Newton, according to both AccuWeather and Weather.com.

But in front of the Newton Police Headquarters in West Newton, it was 99 degrees. Across the city in the Bloomingdale’s parking lot in Chestnut Hill, it was 99 degrees.

Meanwhile, just outside the Allen House in West Newton and Boston College’s Stokes Hall in Chestnut Hill—two areas flush with trees and grass—the temperatures were 93 and 94 degrees, respectively.

This variance is an effect of two things: pavement radiating heat and plant life cooling the air. And Newton—with its diversity of neighborhoods and villages—is scattered with heat islands and green oases, showing the importance of greenery in urban planning.

The city has taken more and more notice of this, and Newton is working to calm its heat islands with the cooling power of trees.

When trees drink, air cools

It’s well-known that trees help cool the air, but how do they do it?

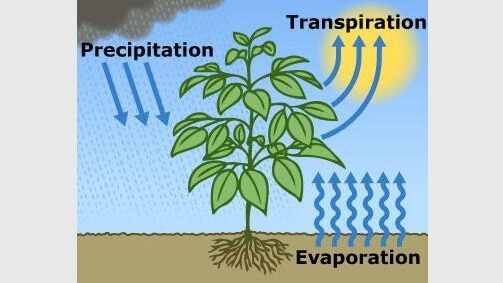

“Whenever you’re planting trees, it’s going to keep that area cooler, because the trees are going to be reflecting sunlight from the surface, and they’re also going to be evaporating water during the day,” Richard Primack, Newton resident and biology professor at Boston University, said.

This process of moving water from the roots to the air is known as “evapotranspiration.”

It’s not just trees. Water evaporation and the resulting cooling comes from shrubs, flowers and grass, too.

An even clearer example can be seen in Upper Falls. On Aug. 5, while the official temperature was 90 degrees, the air at Hemlock Gorge Reservation was 86 degrees. Just about 100 feet away feet away on the side of Route 9, the temperature was 98 degrees.

Trees are a year-round blessing. With leaves off the trees in winter, more sunlight can get past the trees to the buildings near them, adding a natural warming effect.

“So the trees really reduce heating costs during the wintertime and also reduce air conditioning costs in summer,” Primack continued.

Newton’s hot spots

Buildings, streets and sidewalks, in contrast, absorb and radiate heat and keep the areas around them warm. Putting a cluster of buildings and pavement in one area can create what’s called a “heat island.”

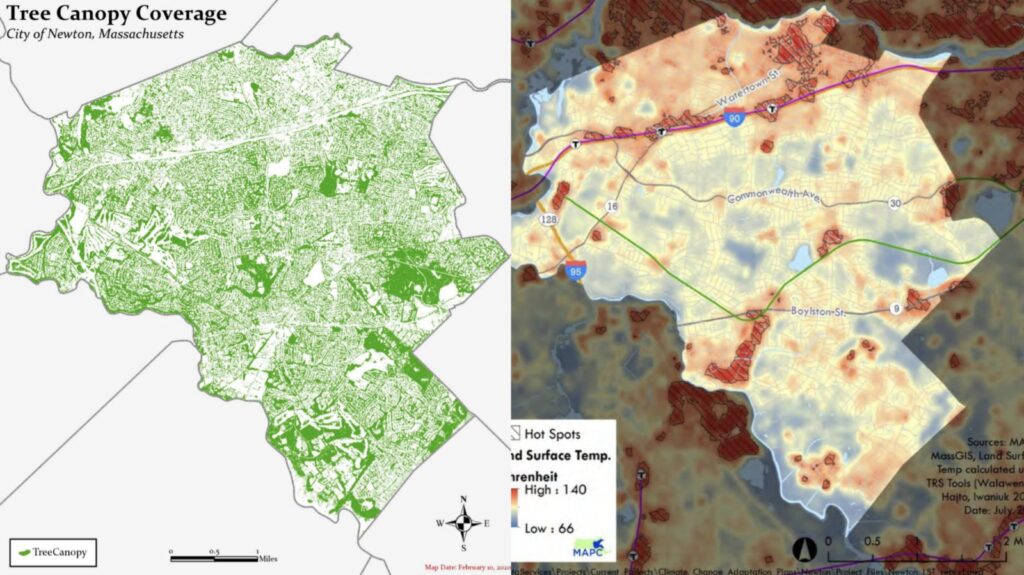

And Newton has quite a few heat islands. A map created by MAPC (a regional urban planning agency) for Newton shows the Garden City has huge heat issues along the Massachusetts Turnpike.

Air cooling and combatting heat islands were taken into consideration when the city developed its street tree planting plan several years ago, according to Marc Welch, Newton’s director of urban forestry.

“To help determine where the first places were that we would plant, we had aerial maps of the city that showed us where the greatest heat areas were,” Welch said. “We also had maps of canopy gaps, where there are less trees. We specifically used this to target our planting areas in general locations where there’s less canopy and higher incidences of heat island effect.”

Since 2015, Welch continued, the emphasis of tree planting has been focused on heat islands.

“In many instances, they are locations where buildings tend to be closer together or there are parking areas,” Welch said.

There’s a plan underway—the Washington Street Vision—to transform a stretch of Washington Street in West Newton with roadway and sidewalk safety improvements as well as landscaping enhancements to create “a boulevard with a strong emphasis on trees and landscaping.”

“One of the goals of this Vision is to create a network of new small parks and plazas, to reinvigorate existing park space, and possibly to create new village greens over the Mass Pike for both West Newton Square and Newtonville Square,” the Washington Street plan reads.

With the Washington Street plan and a similar roadway renovation project on Walnut Street, the city expects to add a combined 80 new trees to West Newton and Newtonville’s village centers.

“Whether it’s trees or other vegetation, anywhere there’s vegetation it’s going to help improve and mitigate the heat or improve the environment in the air,” Welch said.

Trees certainly have a bigger impact, given their size and the fact that they provide canopy. That was seen in the Aug. 5 temperature variances: Newton Center Green, surrounded by pavement and buildings and covered in grass but with few trees, was 116 degrees in the shade.

That was still cooler than it could have been. Nearby, the parking lot behind Johnny’s Luncheonette was a staggering 126 degrees.

The roots of loss

Newton currently has 20,000 street trees and “Countless trees on public property,” according to the city’s website. It’s lost a lot of tree canopy in recent decades, though, and the city is now focused on regrowing its urban forestry.

The City Council recently passed a tree ordinance—similar to ones in Cambridge, Wellesley and Lexington—requiring homeowners to pay a fee when removing trees from their yards.

How does tree loss get so out-of-control?

In many cities, tree canopy and heat islands are seen as equity issues. In the past, cities approved high-density housing with little or no greenery in low-income neighborhoods while affluent areas were lush with trees and fields.

“It’s a dramatic difference in places like Boston,” BU professor, Primack said. “There are poor neighborhoods in Boston, often neighborhoods of color, where there are relatively few trees and it’s just much hotter in the summertime. And areas which are wealthier and have a higher proportion of white people in the population, they often have more trees and it’s a more enjoyable environment.”

In Newton, however, that hasn’t been the case. Newton’s street tree population has declined in recent decades, Welch said, but it’s declined evenly throughout the city.

Rather than income-motivated bias, the city has just seen a lot of development in recent decades. So while the Trio apartments in Newtonville may be high-end, they’re in the middle of a heat island.

And the city has been working to rectify heat island issues left in the wake of so much growth, Welch explained.

“Our planting practices in the past were pretty uniform throughout the whole city,” Welch said. “At one point, on most streets in the city, if there was a plant-able location, a tree was planted. And at one point, every street was full of street trees.”

City officials are working to get Newton back to its former foliage glory, with more street trees and with greenery incorporated into as many projects as possible.

Regardless of race or economic background, trees are a tool for improving life because they not only cool and clean the air, they also make people happy.

“Trees make a more enjoyable environment,” Primack noted. “And there are many studies that show that when people live in environments with a lot of trees and other plantings, they actually feel happier and more relaxed and suffer from less stress and anxiety.”